EPCAMR Staff feels this is the most extensive recount of coal mining impact on those who live in and work in the coal region by a newspaper investigation. Thank you, Scranton Times, for working with us!

Investigation Navigation

________________________________________

Part 1 – 1/30/2005

Too Many Mines, Too Little Money

State Program Trying To Make Up for Lost Federal Contributions

Part 2 – 1/31/2005

Danger Lurks in Mines

Part 3 – 2/1/2005

Mining for Solutions

Competing Plans

Successful Reclamation Results are All Around

Orange Water, Silver Lining

________________________________________

Region Waiting To Reclaim Scarred Land: Too Many Mines, Too Little Money

BY JESSICA D. MATTHEWS THE SUNDAY TIMES 1/30/2005

Growing up in her family’s Carbondale house, Jacqueline Hemak had to navigate a grid of planks to do laundry and other chores in the basement. Everything, including the washer and dryer, sat on concrete slabs to avoid getting ruined by the orange water that would regularly seep through the floor from a nearby abandoned mine.When her mother died in 2001, Mrs. Hemak and her brother, George Bates Jr., had enough. Mr. Bates spent $20,000 to have the family home lifted and temporarily moved. They had a new foundation built for the house — raising it about eight feet off the ground and solving their flooding problem.

Flooding from mine runoff has plagued other homes in their Park Street neighborhood for decades. State and local officials routinely told residents there is little that can be done.

There are more abandoned mines to clean up than available money.

They must wait their turn.

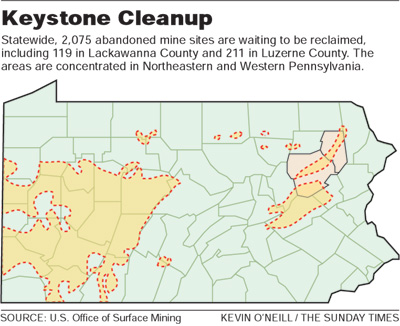

Statewide, 2,075 abandoned mine sites are waiting to be reclaimed, including 119 in Lackawanna County and 211 in Luzerne County. Across the nation, a backlog of more than 9,400 abandoned mines compete for limited federal dollars dispersed through the Abandoned Mine Lands program.

And those are just the sites inventoried by state and federal governments. State and federal officials admit their inventory lists are incomplete.

More than $8.6 billion is needed to cleanup inventoried abandoned mines nationwide. Pennsylvania has more than half of that total, with a need of $4.9 billion.

Yet the federal program created to fix the deadly and dangerous conditions left by abandoned coal mines places less than half its money into those problems because of loopholes in the law and a lack of federal oversight, a Times-Shamrock newspapers investigation found.

In addition, the review shows:

Money earmarked to clean the most dangerous abandoned mines has been spent on general environmental problems and lower-priority projects.

Money supposed to automatically go to states and Indian tribes has not been distributed and is instead being used to balance the federal deficit.

Cleanup funds have been used for roads, hospitals, school-building projects and water systems.

“It’s just a poorly administered and inefficient program,” said U.S. Rep. Paul E. Kanjorski, D-Nanticoke. “There is not sufficient funding. It’s a program that has had massive misuse of money.”

MORE TO BE DONEThe federal government established the Surface Mining Control Reclamation Act in 1977, creating the Abandoned Mine Land fund. Today, fund money comes from a tax on coal operators — 35 cents per ton of surfaced mine coal, 15 cents per ton of underground mined goal and 10 cents per ton of lignite, or brown coal.

The federal government distributes the mine cleanup money to states and tribes for planned and emergency mine cleanups.

The federal government distributes the mine cleanup money to states and tribes for planned and emergency mine cleanups.

The program was set to expire Sept. 30, but Congress extended it until June 30. Lawmakers must now decide whether to eliminate the tax, reauthorize it as is or to make alterations.

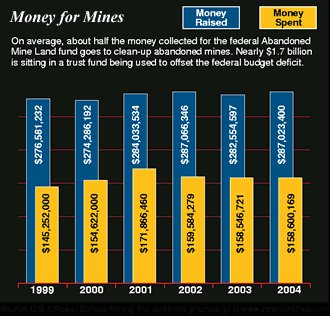

The coal tax generated about $287 million last year — the majority coming from coal companies operating in Western states.

Of that money, half is supposed to go back to states and Indian tribes for cleanup projects each determine. But they received roughly 27 percent of the total, with 26 states and three tribes getting nearly $78.2 million.

The balance of the cleanup money is distributed for specific mine projects and is used for administrative programs costs. From that pool, Pennsylvania receives about $25 million a year. Lackawanna County gets about $2.9 million, while Luzerne receives about $2.2 million.

Locally, the money has been used to repair hundreds of abandoned coal mine problems, including filling hazardous mine openings, cleaning up clogged streams and removing hazardous equipment and waste.

Nearly 4,500 acres of scarred land in Lackawanna and Luzerne counties have been regraded and replanted with program money. More than 1,600 acres of subsidized land has been sustained. Just about 26 miles of dangerous highwalls have been removed.

Nationwide, more than 265,000 acres of abandoned mines have been reclaimed.

There is still much more to be done.

Just about half of all Lackawanna County’s abandoned mines and 14 percent in Luzerne have been reclaimed. With growing competition for limited mine cleanup dollars and a price tag of $500 million to reclaim the rest of the listed sites in both counties, the outlook on getting the job done anytime soon is grim.

Since 1978, coal companies have paid about $7 billion into the federal fund. Yet, more than $1.7 billion is sitting in a trust fund, the newspapers found.

The Abandoned Mine Land fund is “on budget,” which means the money is held in a treasury pool and used to help balance the federal budget. Only Congress can release the money.

In total, states are owed more than $981 million. Pennsylvania is owed nearly $56.3 million. Wyoming is owed the most — about $400 million.

Additionally, since 1996 Congress has also spent more than $665 million of interest from the cleanup fund on health care benefits for thousands of retired miners to bail out the collapsing United Mine Workers of America benefit fund.

That may not have been what the money was intended for, but it is necessary, said Stan Geary, a spokesman for the Pennsylvania Coal Association. Without the money, thousands of retired mine workers would be without benefits, he said.

“The coal industry has paid over $6 million in the AML fund since 1977,” said Carol Raulston, a spokeswoman for the National Mining Association. “Only half of it has gone to clean up high-priority problems. This is not how this money was envisioned to be spent when the program was created.

“There needs to be greater emphasis on cleaning up the higher priority abandoned mine sites,” she said.

GREAT DIVIDEDespite the need to clean up dangerous abandoned mine problems, $1 in every $10 of program money is being spent on noncoal projects, the newspapers found.

In Wyoming alone, nearly $93 million has been spent on building and repairing roads, public utilities and infrastructure projects courtesy of a loophole in the federal law. The projects include $12 million on a high school addition, nearly $12.7 million on road repairs, and almost $17.9 million on a University of Wyoming geology building.

“They are living the life of Riley out there in Wyoming and some other Western states,” said Bernard McGurl, executive director of the Lackawanna River Corridor Association. “They don’t want to send the money back East where it’s desperately needed for mine reclamation. So Pennsylvania has backlogs of dangerous mines that need to be reclaimed while they’re (Western states) building new schools.”

However, the noncoal spending with federal cleanup money is legal, said Evan Green, an administrator at the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality.

“We certainly understand the needs of the Eastern states,” he said. “But everything Wyoming has spent money on is legal. Whether it was a wise choice or not, it’s not fair to be critical of Wyoming for addressing its building needs when it’s legal.”

The majority of federal mine cleanup money Wyoming received was used to fix problems indirectly or directly caused by mines, he said.

Like other Western states, Wyoming did little coal mining before 1977. States west of the Mississippi River mined about 165 million tons of coal in 1977. That compares with nearly 600 million in 2004, or more than half of the nation’s annual coal production.

As a result, Western states now contribute the bulk of cleanup fund money. Wyoming collected $135 million in mine reclamation taxes last year about 47 percent of all tax dollars.

Cleanup is also different in Western states, where strip mining — rather than deep, underground mining — is the rule. Reclamation of such mining is far cheaper, with matters like subsidence less of an issue.

To address concerns that states paying the most have the smallest inventories of mines to be reclaimed, lawmakers changed the law: If a state reclaimed its abandoned mines, it could become certified and then spend cleanup money on construction projects in communities impacted by coal development.

Wyoming was the first state to certify in 1984. Montana and Louisiana were next.

However, in 1991, the U.S. General Accounting Office found the Office of Surface Mining and officials in Louisiana, Montana and Wyoming wrongly received certification. The three states had cleaned up their most serious abandoned mine problems but lower-priority problems remained.

Congress tightened up the law to say states must show “all” coal mines were reclaimed in order to broaden their spending. However, lawmakers “grandfathered in” Louisiana, Montana and Wyoming, so the states could continue to spend cleanup dollars on noncoal projects. They also allowed certified states to use the money on public works projects.

Even so, the states have been adding newly discovered abandoned mine sites to the list for additional mine cleanup funds. Wyoming currently has nearly $43.2 million in such unfunded projects.

Mr. Green expects Wyoming to add more abandoned mines to the federal inventory list — possibly as many as 1,000, with an estimated cost of $60 million to reclaim.

“Who knows what the philosophy or motivation was when Wyoming got certified in 1984,” he said. “That’s water under the bridge. ”

Wyoming should continue receiving mine cleanup money because the state contributes most of the revenues into the federal fund, he said.

“It’s a Catch-22,” said Rod Fletcher, director of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation. “You would like to see the (Abandoned Mine Land) money go where it is needed most. But the Western states are today’s largest coal producers. They want a piece of the pie.”

SETTING PRIORITIES

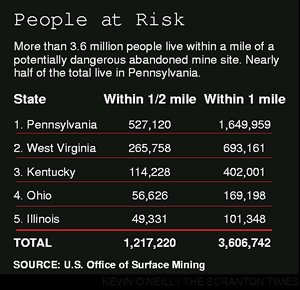

Nationwide, 3.6 million Americans live less than a mile from health and safety hazards created by abandoned coal mines, according to a 2003 report issued by the U.S. Office of Surface Mining. That includes about 1.6 million people in Pennsylvania, or more than 40 percent of the total.

State and local experts say the numbers in Pennsylvania are even higher.

“Pennsylvania has many abandoned mine problems because the funding to clean them up is so limited,” said Mr. Fletcher. “Many of the problem areas are in populated places so naturally there are large numbers of people living close to these sites.”

Despite the report findings, nearly $283 million has been spent on fixing lower-priority abandoned mine problems nationwide while higher-priority problems that threaten public safety and health remain unfunded, the newspapers found.

The federal government classifies abandoned mine problems into five priorities, with those that pose the most danger to public health and safety ranked highest. Most lower priority problems are environmental-related, such as water runoff concerns, rather than structural- or land-related.

In Pennsylvania, lower-priority problems that received funding were in connection with higher-priority projects that posed serious public risks, said Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Secretary Kathleen A. McGinty.

“You wouldn’t just go in and do half a project,” she said. “If there are peripheral (lower-priority) sites, you would want to fix them, too. It would be less expensive than having to go back in and clean it up later… Every AML project in Pennsylvania is very carefully and stringently reviewed by the DEP.”

To date, Pennsylvania has spent more than $350 million cleaning up its higher-priority problems, Ms. McGinty said.

The newspapers’ analysis of the $5.4 million in federal funds that went to clean up lower-priority sites in Lackawanna and Luzerne counties found all were in conjunction with higher-priority abandoned mine sites.

The Office of Surface Mining, however, does not keep records on whether a lower-priority project was completed in conjunction with a higher-priority one. Furthermore, federal oversight of how the funds are spent is lax. States make the priority determinations on abandoned mines, and there are no requirements for priority lists for states to strictly adhere to.

For example, of the $235.4 million spent on mine reclamation projects in Illinois, nearly three-quarters, or about $171.3 million, was spent on lower-priority projects, the newspapers found. The state currently lists more than $54.6 million higher-priority projects still needing funding.

In Indiana, nearly half of the $98.3 million spent went to lower-priority projects, the newspapers found. The state currently lists more than $12.5 million higher-priority problems waiting for funding.

“States basically pick the sites that get funding,” Mr. Kanjorski said. “Federal oversight is marginally there. Some states are really out of control because the administering of the program is so bad.”

At one time, the Office of Surface Mining conducted three inspections on every state project one before money was given, one during and one after reclamation. Now, states are given a block of money up front based on general descriptions of the projects. Federal inspections are now random.

“There are too many projects,” said Fred Sherfy, a regulatory specialist with the Office of Surface Mining’s Harrisburg bureau. “We just don’t have the staff anymore.”

In the last year, the Office of Surface Mining conducted about 40 site inspections on cleanup projects in Pennsylvania during and after construction, he said. About 109 projects were inspected before work began.

“Is it an ideal situation?” Mr. Sherfy asked. “No. But it’s the best way it can be done at this time.”

Justin Taylor walks along the 200 block of South Park St. in Carbondale where water runoff from mines has been a problem and is sladed for corrective measures. (Michael J. Mullen)

Back on Park Street in Carbondale, the waiting game is nearly over for neighbors. After decades of begging for money to fix flooding problems caused by abandoned mines, federal money and county dollars have been freed up.

“We will regrade the area and restore it to approximately what it looked like before it was mined,” said Patricia Acker, project engineer of Acker Associates in Moscow.

Ms. Acker did not know the exact cost of the project. Early estimates place it at about $10 million. She expects bids for the project to be out by the end of the year. Work should be completed within two years.

For Mrs. Hemak, raising the family house and building a higher foundation was a quicker fix to basement flooding problems. She is looking forward to having a flood-free front yard once the project is done.

©Scranton Times Tribune 2005

Pingback: Big Oil Has a Plan to Turn Appalachia Into Hydrogen Country